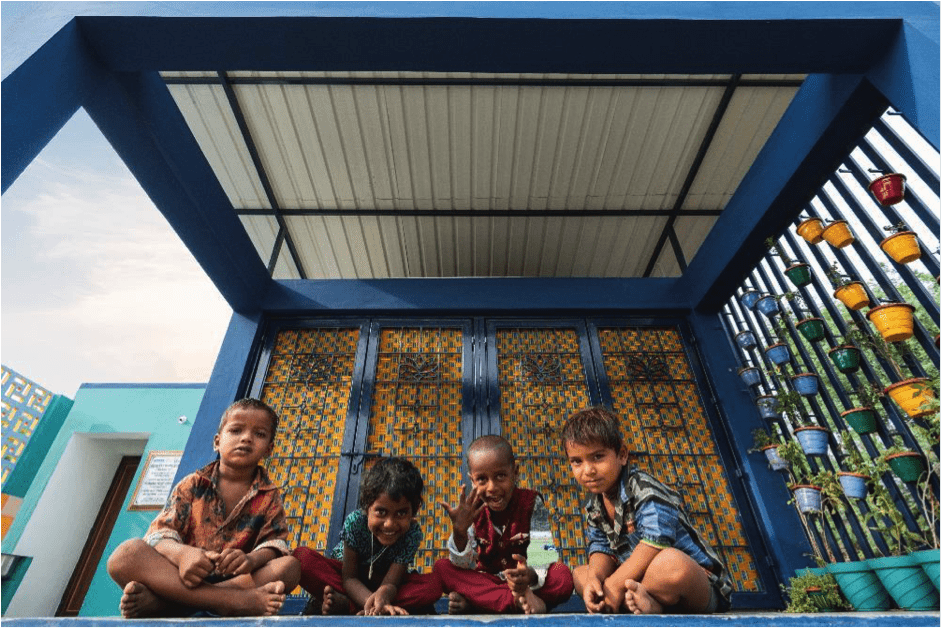

Image credit: Roberto Rodriguez Reyes, @rober3

The following is an excerpt from MoDDD graduate Sarah Schoffel’s article for The Design Between, a collaborative publication focusing on the issues of disaster, design and development founded by MoDDD alumni.

In a world of increasingly changeable external forces, how do you engage with a community, overcome cultural and language barriers and build enough trust to realise a project together?

I recently had the opportunity to experience answers to these questions by volunteering in India for six months. Through the Anganwadi Project (TAP), I worked alongside fellow architect Allison Stout, the community of Bondalawada and local partner Rural Development Trust (RDT) to design and build an anganwadi in rural India. Anganwadi means ‘courtyard shelter’ in Hindi and, since 1975, has come to mean a preschool or early childhood centre. TAP is an Australian NGO founded in 2006 with the specific goal of building anganwadis in disadvantaged communities in India.

The importance of preschools

Preschools seed community connections. In rural India especially, where brides leave their own family networks to move to their husband’s village, the bonds formed with other women around motherhood – with sisters in law, friends and ‘aunties’ – are crucial to each young woman’s quality of life and to her agency within her new community.

The direct impact of preschools on children’s lives in developing countries is well researched, but anganwadi teachers do much more than teach. Alongside education they provide vital nutrition to children, babies, nursing or expectant mothers and older women. They record growth statistics and act as vaccination centres. They teach parents about children’s health, nutrition and the importance of ongoing education. They create safe environments for young children so their mothers can take on employment without anxiety. In many cases they develop programs for mentoring teenage girls and they reinforce and strengthen the all-important bonds between women of the community.

Engaging the community

TAP is all about immersion. There’s no quick ‘fly in fly out’. Volunteers work with the community from day one until the delivery of the anganwadi. This approach has many obvious advantages such as a deeper understanding of the community’s hierarchies and internal structures but most importantly it grows trusting relationships. TAP’s approach is built on the experience that active participation generally improves design outcomes, uses local resources and makes projects more sustainable.

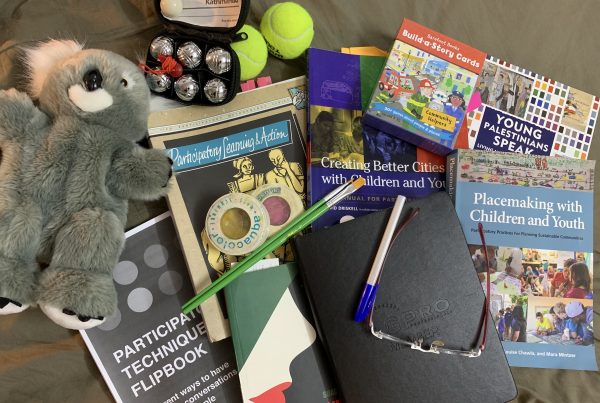

From the outset it was our intention to engage the teacher, children and wider village in the most authentic participatory process possible. We used many different participatory techniques for engagement but soon discovered that a foolproof way to engage community members was simply to ‘sit and do’, essentially to start doing something, anything really – writing, sketching, mapping, designing, drawing, making things – even playing games. Visibly engaging in activities invited curiosity and participation even when language barriers didn’t allow for much explanation.

Image credit: Roberto Rodriguez Reyes, @rober3

What we created together

At the end of the day we completed a robust little building that is cool, colourful and useful. We made lasting friendships in the Bondalawada community and we galvanised the community for a while on a collaborative project. I think its process and its impact may be transformative at least in the lives of those involved. The women and children especially, were empowered and in a way that’s difficult to pinpoint – social structures shifted a little as many individuals reassessed their capacities. Over time it will touch the lives of hundreds of people within the community and many of them, adults and children alike, will remember building it.